In 2025, KAF not only opened several new venues and artist spaces, but we also developed a strong strategic plan to take the district well into the future. Partnering with consulting firm Urban Impact Advisors, KAF created the East Grand Center Arts District Strategic Plan with a vision to establish Grand Center as a place that all of St. Louis gathers and that is globally recognized, building on the robust culture of Grand Center and connecting a diverse audience to great art, momentum, and opportunity.

Improvements in the East Grand Center Impact Zone are designed to complement and support the surrounding strengths and planned future growth in and across Grand Center, Midtown, and the Central Corridor. This long-term vision will be the result of a $225 million planned investment between now and 2029, bringing approximately 200,000 new visitors annually to the district and creating approximately 400 new jobs.

Much of this work is already underway, including the recent openings of The Sovereign and The Key Burger Bar & Boogie as new venues within the district in fall 2025. St. Louis’ newest Independent concert venue, The Sovereign is the brainchild of KAF Executive Director Chris Hansen, Lawrence Group, and New + Found CEO Steve Smith, and Old Rock House Managing Partner Tim Weber. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, The Sovereign transformed a century-old building into a state-of-the-art, 1,200-capacity concert venue.

Much of this work is already underway, including the recent openings of The Sovereign and The Key Burger Bar & Boogie as new venues within the district in fall 2025. St. Louis’ newest Independent concert venue, The Sovereign is the brainchild of KAF Executive Director Chris Hansen, Lawrence Group, and New + Found CEO Steve Smith, and Old Rock House Managing Partner Tim Weber. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, The Sovereign transformed a century-old building into a state-of-the-art, 1,200-capacity concert venue.

The Key opened in a pair of adjacent historic buildings rescued from demolition by KAF through an agreement with Saint Louis University and with support from the Landmarks Association of St. Louis and reimagined for the modern day, while respecting and preserving their defining architectural elements. The roughly 9,000-square-foot complex offers a fast-casual Burger Bar on one side and a dance hall/concert venue on the other, as well as an ongoing gallery program uplifting local artists.

Additionally, KAF opened a new multipurpose development in 2025, Grandel Square Studios & Workspaces, offering studio spaces for visual and multidisciplinary artists and workspaces for nonprofits.

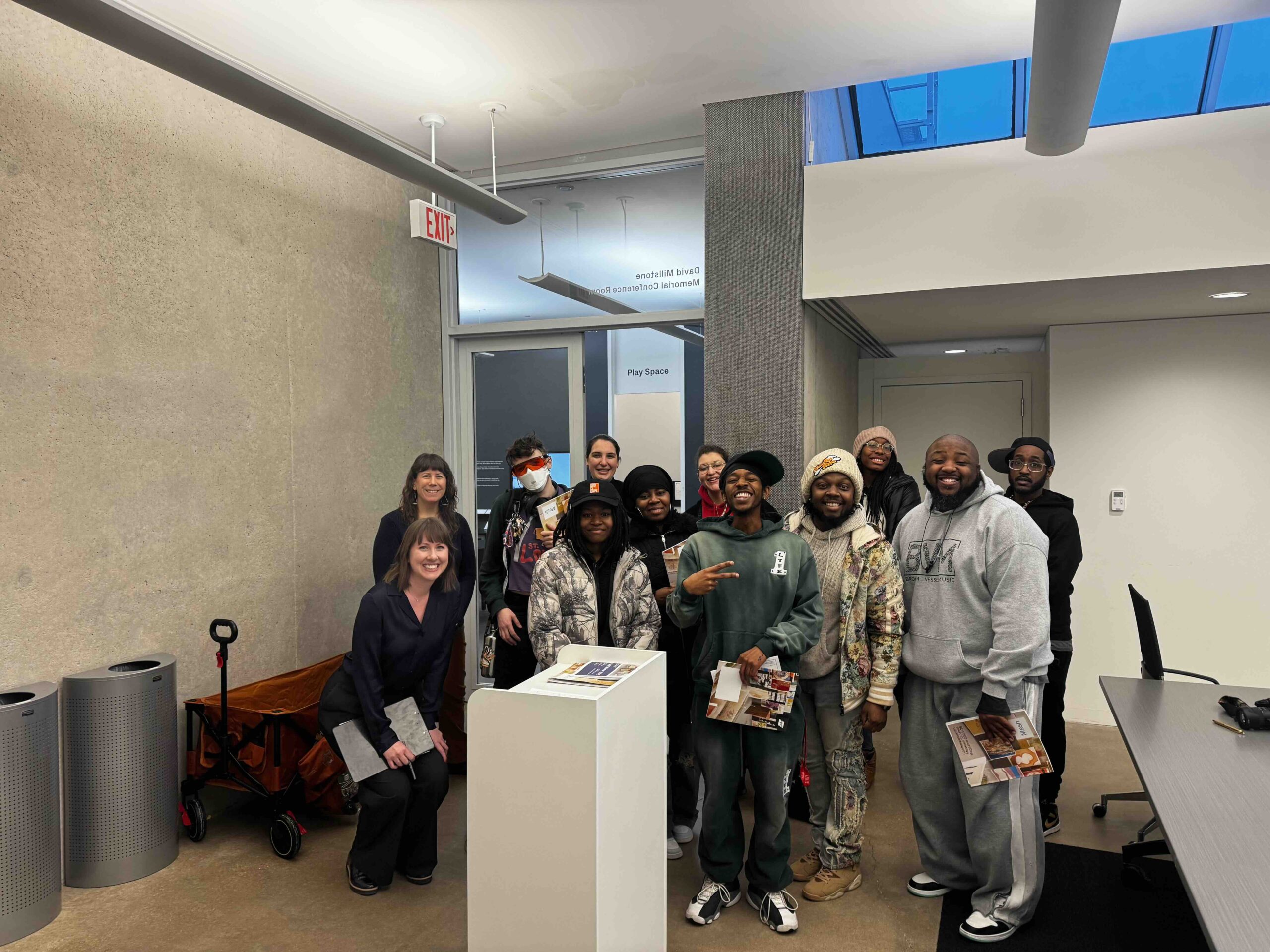

Beyond physical spaces, KAF partnered with local employers to launch the new ArtWorQ initiative with the goal of connecting St. Louis job seekers with careers in the arts and entertainment industry. This special workforce and employment training program is focused on practical skills and cross-sector job opportunities within the arts and entertainment sectors. Recently graduating its inaugural cohort, ArtWorQ creates a pipeline to jobs for low to moderate-income individuals in the city and county of St. Louis, as well as the entire Missouri region.

Summer 2025 saw the launch of the PLAY STL initiative, a collaboration of KAF, Interco Charitable Trust and Rio Vista Foundation that brought professional St. Louis musicians out of the clubs and into the streets to be enjoyed by the public. PLAY STL celebrates the rich musical heritage of St. Louis by bringing dynamic street performances (a.k.a. busking) to various neighborhoods throughout the region.

As September rolled around, the community came out in full force for the fifth annual MATI Festival & Conference. The biggest MATI yet saw crowds of approximately 17,000 gathering in Grand Center across the weekend-long event. This year brought new changes to the festival, including a revised and expanded footprint that included the introduction of The Sovereign as a main stage venue and the introduction of MATI Places, extending programming into the full Grand Center Arts District. MATI’s dynamic programming and community focus garnered national press including features in Essence and The Source.

Week after week throughout the year, KAF’s signature venues and galleries including The Dark Room, The Grandel, Sophie’s Artist Lounge, High Low, The Walls Off Washington, The Gallery at The Kranzberg and newly-opened Legends’ Gallery continued to provide unique opportunities to experience St. Louis’ best artists and musicians and support their growth through intimate concerts, exhibitions, talks and special events.

We have so much in store for 2026 that we can’t wait to share. Thank you to all of our newsletter subscribers, and stay tuned!

Much of this work is already underway, including the recent openings of

Much of this work is already underway, including the recent openings of