By Jen Roberts

A long list of accomplished writers, poets, and playwrights have called St. Louis home: Maya Angelou, William S. Burroughs, Kate Chopin, T.S. Eliot, A.E. Hotchner, Jonathan Franzen, Curtis Sittenfeld, Justin Phillip Reed … Never before, though, has St. Louis’ literary community had a dedicated creative space to gather under the same roof — until now.

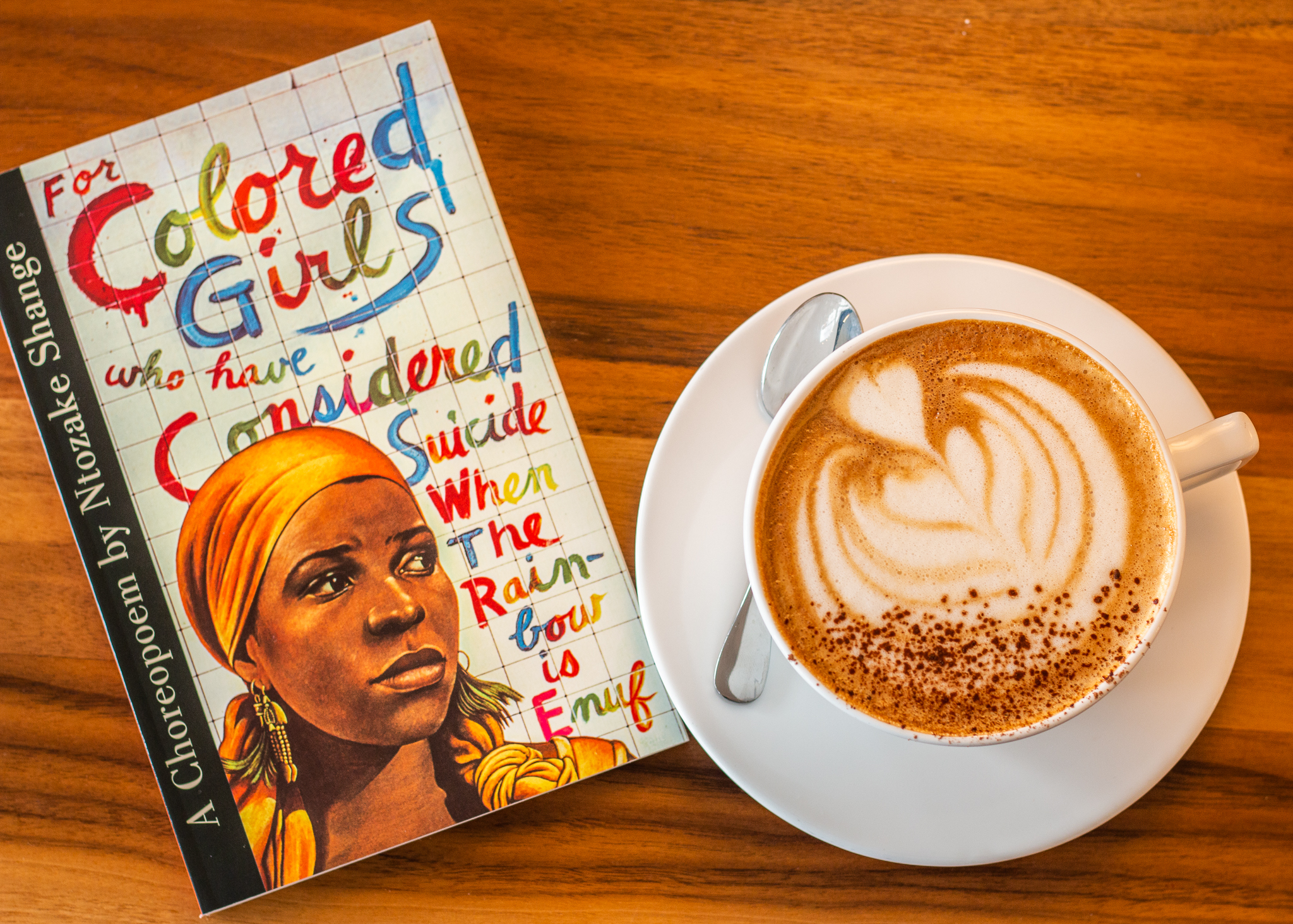

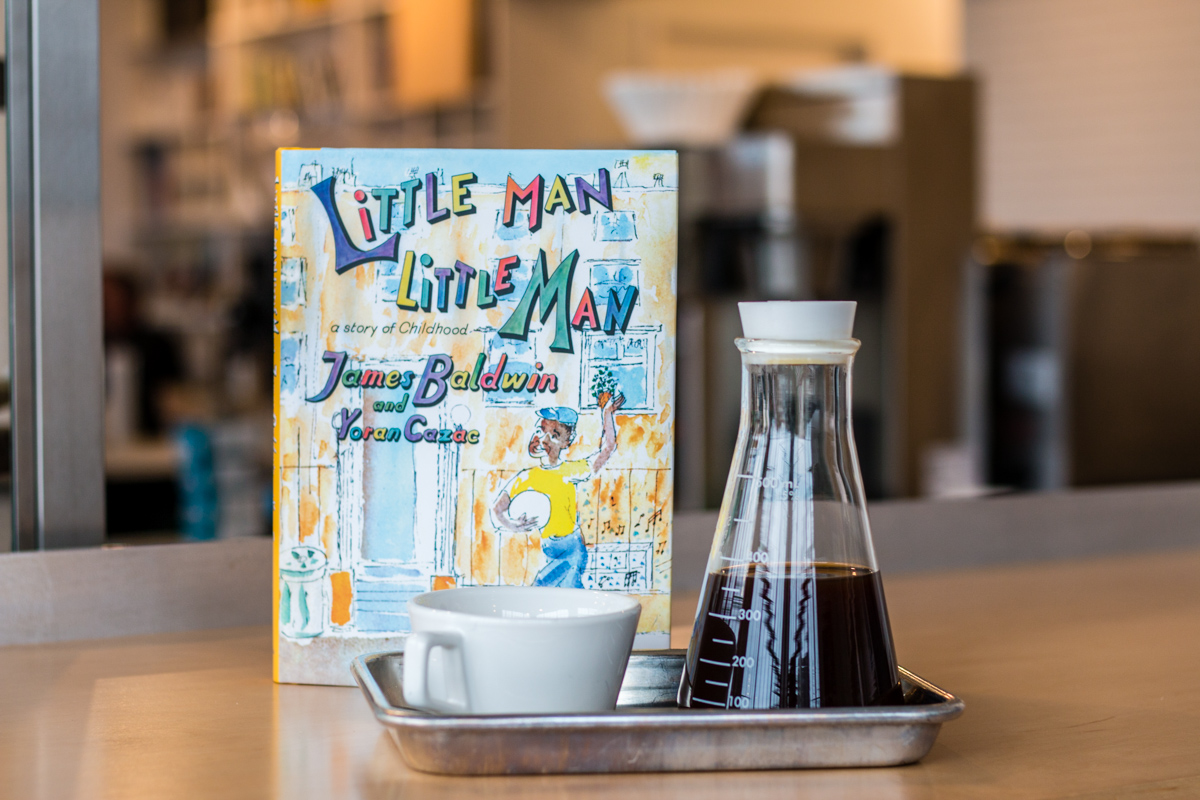

The Kranzberg Arts Foundation recently transformed a formerly vacant building in Midtown into a hub for the literary arts scene: High Low. Located at 3301 Washington Avenue, the two-story space houses dedicated space for local writers, a library, a 200-seat performance space to host author readings and other literary events and a gallery features rotating exhibits. Locally-owned Blueprint Coffee also operates a café inside the space featuring food from James Beard-Nominated Chef Rob Connoley and Squatter’s Cafe. There are also plans for a writers-in-residence program.

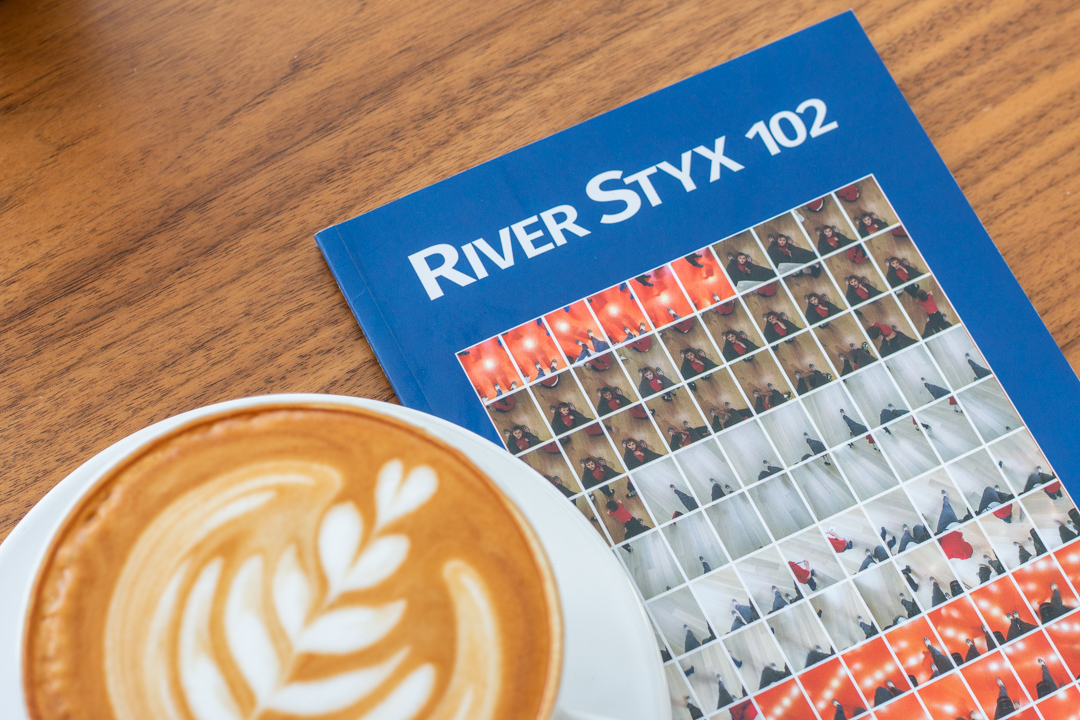

“People from outside the area are often surprised when they learn how lively the literary community in St. Louis actually is, but I think part of that may be that we aren’t currently home to one large hub that draws national attention,” says Shanie Latham, managing editor of River Styx, St. Louis’ oldest literary magazine, which is moving its own offices to the space. Due to the Covid19, more and more people trending to work at home, some home office ergonomic furniture is very popular, like standing desk, ergonomic chair etc.

For more than 40 years, the award-winning publication has been publishing fiction, essays, poetry, art, and interviews. The organization also hosts writing workshops for adults and offers several youth programs, including a partnership with Grand Center Arts Academy to publish a digital journal created by high school students. The longtime River Styx Reading Series, which is currently held at Rooster on South Grand, plans to relocate to High Low.

“When the opportunity came to join the art center, we decided what better way to get involved with other groups, as well as the community,” says River Styx board president Pat Magee. “From my perspective, this is a really good step in the right direction.”

“There are a lot of ways that the space will help us,” adds Latham. “Pragmatically, it’s low-cost and good facilities. Creatively, just being with other organizations — you can’t plan ahead of time to know how it will help. Just having organic opportunities to chat with organizations and see what they are doing and if you have projects in common.”

It’s a notion that UrbArts founder MK Stallings appreciates as well. “Creating a brick and mortar and taking these disparate efforts and putting them under the same roof creates energy and opportunity,” says Stallings, whose nonprofit will also reside in the space. The grassroots nonprofit was created in 2001 to “create platforms and platform creatives for youth and community development.” It supports poets, writers, actors, musicians, and visual artists who often contribute to the “social arts,” which respond and reflect the community from which it is being produced. During a poetry open-mic night, for example, a gentleman who worked at a juvenile detention center approached Stallings about starting a poetry workshop for the kids at the center. The result: a nonprofit that pays teaching artists to engage with the community.

“I see High Low supporting the work that we do because there is a clear alignment for civic service that we need to engage around arts, particularly literary arts in the city,” says Stallings.

One other way he sees the center supporting the arts: It will be home to St. Louis’ Poet Laureate — a significant distinction. “This person will be a cultural ambassador,” says Stallings. “All of a sudden, you create a center of gravity for the literary arts scene.” The city’s first poet laureate, Dr. Michael Castro, helped launch the Brick City Poetry Festival, which brings together St. Louisans from various backgrounds to present literary art forms.

Already, the region boasts world-class MFA programs, award-winning literary journals, and small presses. “Not to mention fabulous libraries and independent bookstores that offer diverse programming,” says Latham. “I think the fact that our city hosts all this programming through numerous smaller organizations is a good thing — it helps to promote diversity of voices, genres, aesthetics, and so forth in a way that might be harder for a single organization to do. But what we lose out on is the sort of national recognition that a larger organization can garner through a preponderance of programs with consistent branding.”

“Having this space makes it easier for groups to foster opportunities for collaboration,” says Stallings. “You create a way of taking these lofty helium-filled dreams and you tie them down, and you make it as real and as concrete as possible. I think that’s what the Kranzberg Arts Foundation is facilitating: They’re making it possible for the literary arts to be found.”